We propose to further develop operational challenges in knowledge production through the concept of disciplining mo(ve)ments. The concept was developed by Tom Holert (2012) in his writings on forms of cooperation in the project-based Polis. Transposed into the problematization of coproduction, disciplining mo(ve)ments occur through de-regulation and networking in the form of projects and appear when positionality is performed as countering viable modes of realizing projects, i.e we can speak of disciplining mo(ve)ments when different understandings of specific project phases or tasks lead to conflict and lead to necessary reiterations of everyone’s understanding of the project.

Working in interdisciplinary teams, or across any other theoretical divide, requires mutual understanding of disciplinary languages and the disposition to communicate. The operationalization of such mutual understandings more often than not relies on trust and an acknowledgement of reciprocity in the process. We have already written about 4P-like projects and programs such as Learning from Las Vegas, co-production or Everyday Urbanism elsewhere in this e-learning arrangement ‘project management in urban design’. We therefore know that both the emerging and existing urban mo(ve)ments are ambivalent: While disciplines enable structurally coherent arguments and perspectives, these must not be confused with structure. What needs to be addressed may not always fall within the scope of existing disciplines, competence and/or budgets of existing organizations and/or actors. The processing of complex dispositions of actors and organizations is a pedagogical and managerial challenge for present and future urban professionals.

Operationalising a concern with the urban

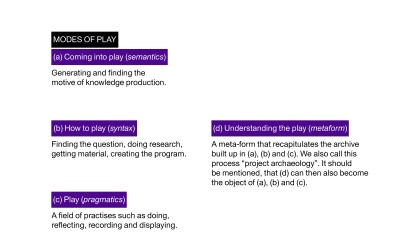

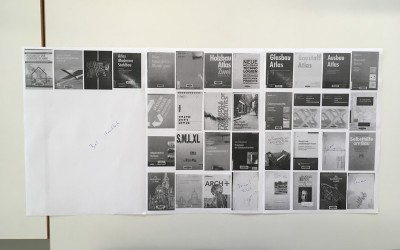

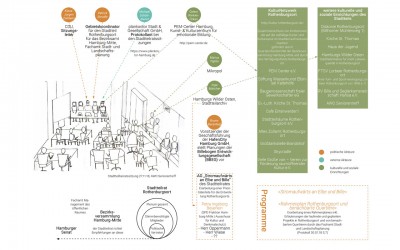

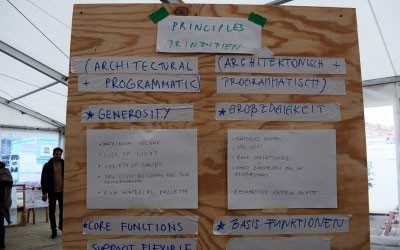

Urban Design at HCU Hamburg as practiced and taught is a relationally interdisciplinary undertaking that – while taking seriously architecture’s promises and problems – aims less at a projected future design (without excluding this option) and instead is more concerned with understanding the coming into being of specific situations, sites and settings and the more or less arbitrary powers that contribute to their existence. It is also transdisciplinary as the team and students work with actors and institutions across and outside of academia. Research, teaching and practice are understood as triad; research and teaching are practiced as much as informed by praxis while practice in turn draws from knowledge produced through research activity and conversely feeds back into teaching. The program speaks to Latour’s notion of ‘matters of concern’ (2004). The concern with the urban – its matters of concern – is motivated by the recognition that we need to understand the conditions under which the architecture of the urban – as opposed to architecture as product alone – is (co-)produced. The urban as relational whole concerns us, it is our motif and engagement with it is a matter of concern and form. Christopher Dell picks up Jacques Rancière’s notion of “scopic regimes” that deserves unpicking: What regulates our modes of seeing, reading and producing the urban and how do we communicate these often implicit agencies?

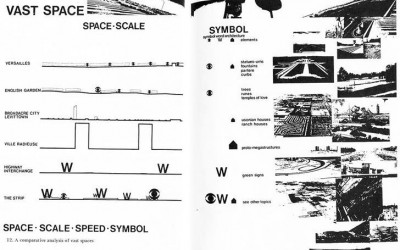

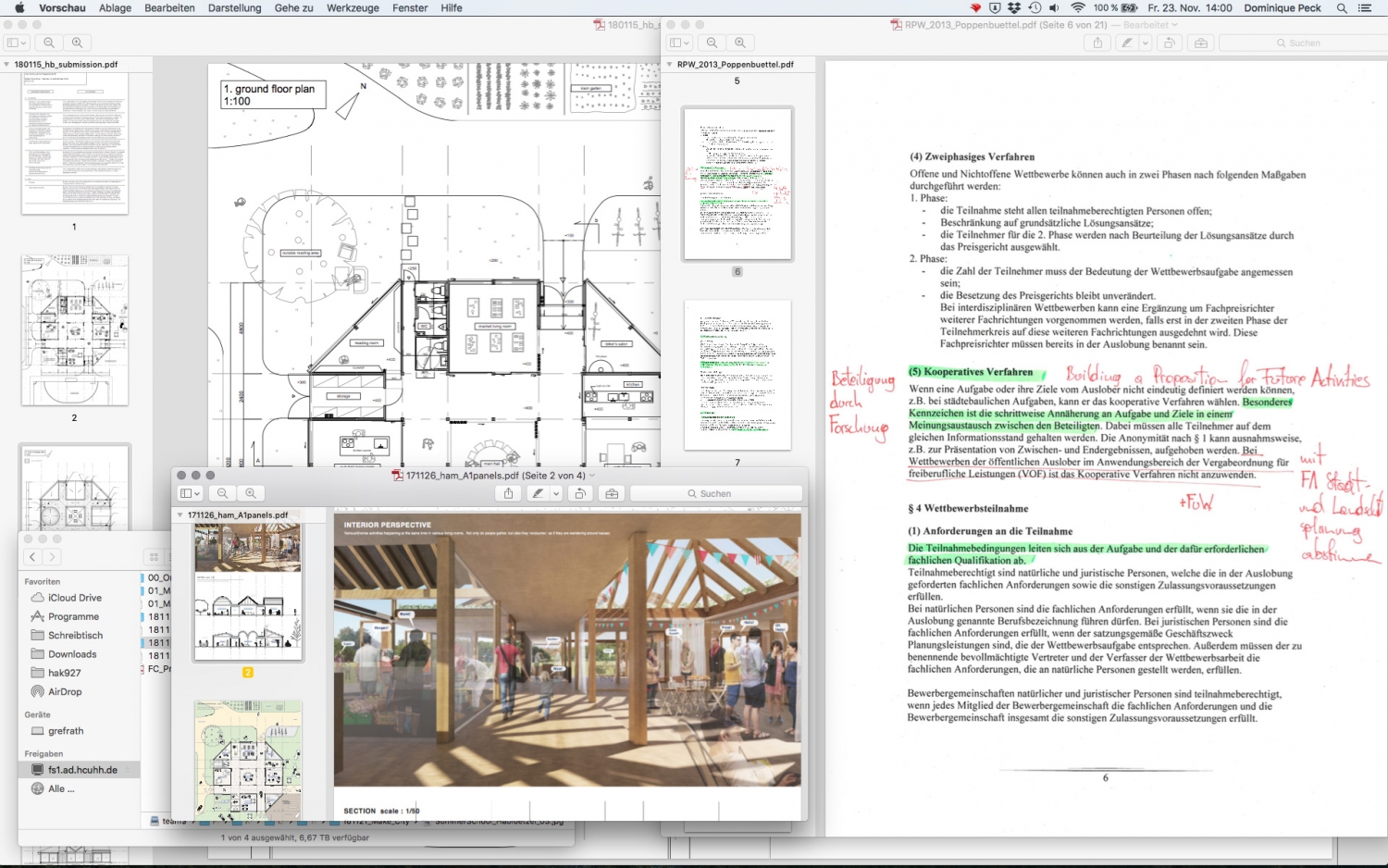

A major motif for urban design overall is to consider how planning interacts with and intervenes into the world under the premise that the production of (urban) space takes place on all scales and cannot be reduced to one disciplinary or scalar perspective given that disciplines and scales themselves are socially constructed and represent transmission belts of organizing the everyday. In this vein, the existing city can be seen as an assemblage of previous and ongoing interventions and future vectors, including plans and contingencies each informed by specific truths or norms. In fact, the research and teaching program Urban Design attempts to open up various scales and perspectives so as to re-assemble different, sometimes conflicting, versions of one reality in their having-becomeness so as to unlock hidden potentials. Led by emerging, yet specific and iteratively developed motifs and relating these individual motifs to urban questions at large as well as issues arising from personal and broader interests, research activities are concerned with both retrospection and projection. The study departs from a deep analysis of a given situation in the now and here (or there) with a view to produce knowledge about common, alternative and new understandings of possible ways to influence particular vectors and possibilities. This approach is a disciplined undertaking in that it is clearly rooted in and drawing on the established disciplines (from which students and staff are recruited) and (at least minimally) structured in its process, while simultaneously disturbing a mono-disciplinary and object-centered approach by working with open form(at)s.

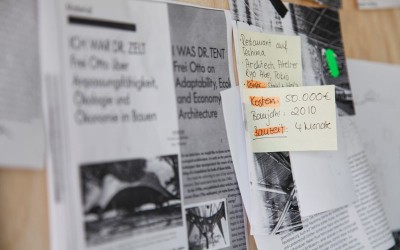

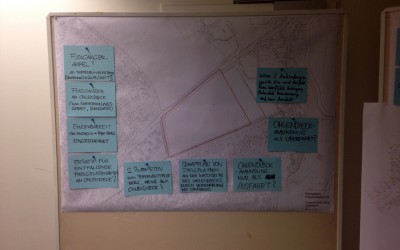

Contemporary planning regulations and regimes disturb or even block the proposed engagement of working with an open form in a minimal structure. Real Politik, legal requirements as well as institutional and managerial resources and responsibilities, often interfere with alternative ways of handling contingency and complexity. Returning to the initial arena in the project Building a Proposition for Future Activities that started with the request for a rendering and turned into a full-fledged model project supported by the city’s integration fund, the various actors involved in the building site proceed according to their schedules and routines, which makes it difficult for an academic team to keep up and take part in organizing and designing the process. Adding to this, the disturbance of schedules and routines is definitely not something that large city agencies and building companies are embracing enthusiastically. Notwithstanding the welcoming of cheap student labor and skilled people who officially figure as “refugees” rather than concrete workers, architects or civil engineers, the participatory planning and construction process proposed by the Urban Design Team as a result of their engagement with forced migration, housing, self-construction, transformation processes and low-budget urbanity has disrupted the situation, even if from another perspective it appears to be disciplined.

Although such draw backs were not new to the Urban Design team, excessive demands in terms of time spent with the project and on site, the organization and preparation of further steps as well as the clearly emerging contradictory interests of involved partners considerably stretched academic members of staff and students alike. Some turns and twists of the ongoing efforts to realize coproduction across hypothetical small and great divides (rather than “just” designing and constructing the building) point to the fundamental contradictions of the urban as practiced. It remains to be seen how the project proceeds, yet these contradictions and conflicts manifest the kind of learning from current urbanism that we need to push further so as to productively re-assemble spatial practices in ways that enhance the coproduction of knowledge.

Note: Individual aspects and ideas of this contribution were first presented at the Architecture Connects conference at Oxford Brookes University and are currently in the process of being reviewed by academics at the time of publication.